At the last Nashville Relic Show, I bought a few fired Spencer bullet casings from a vendor’s junk bin. The casings had been found in New Mexico and the vendor suggested they were from the Indian Wars. The markings on these shell casings can be used to point back to the weapons that fired them just like modern bullet forensic studies.

Spencer rifles and carbines were probably the most common metallic cartridge weapons of the Civil War. There were no equivalent weapons on the Confederate side that could match them in rapidity of fire. Since the majority of Spencer bullets were fired from carbines, they are an excellent indicator of the presence of cavalry.

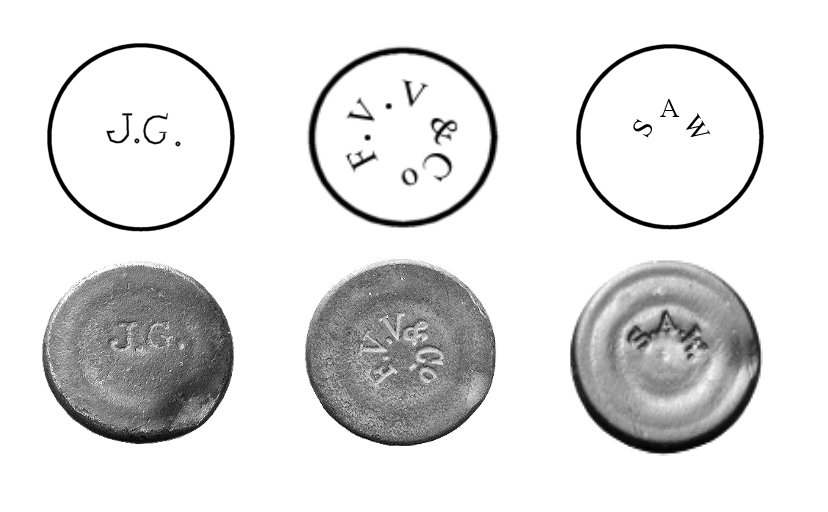

Only known Civil War metallic cartridge headstamps. Beginning in about 1862, Allen and Wheelock and the New Haven Arms Co. (later Winchester) used headstamps.

Whenever one deals with metallic cartridges, one also has to deal with their headstamps. Europeans began headstamping in the early 1860s. With the exception of two cartridge manufacturers, headstamps were never used during the Civil War. Pistol maker Allen and Wheelock of Massachusetts used the raised “A&W” headstamp on their pistol and revolver cartridges in 1862 or 1863. Allen and Wheelock went out-of-business in late 1864. New Haven Arms Company (later Winchester) also used the raised headstamp identification “H” on .their 44-caliber "flat" rimfire cartridges beginning in 1862 for the Henry Rifle.

Initially, rimfire cartridges were manufactured by firearms makers. Cartridges had no headstamps. They were simply assigned a number by the manufacturer to identity the weapon that the cartridges were supposed to be matched to. Firearms makers assigned numbers to their cartridges loosely based upon the diameter of the firing chamber of their weapon.

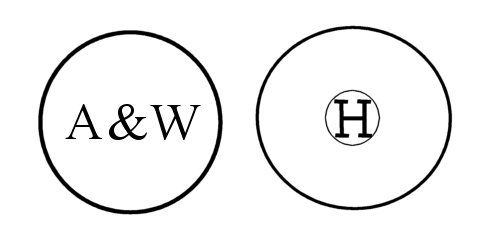

Thus the cartridges that fit the Model 1860 Spencer rifle and carbine were called the "Number 56 Cartridge". This matched the Spencer's chamber diameter of about .56". The actual barrel caliber was .52".

As demand for cartridges increased during the Civil War, the government began to subcontract the manufacture of cartridges away from the arms manufacturers .In 1863, in order to standardize ammunition, the Federal Ordinance Board recommended that the ammunition for several carbines in use at the time be standardized to a single caliber and cartridge type. The new caliber of this ammunition was to be set at .50.

To accommodate these new changes and to differentiate the newer cartridges from the older cartridges, cartridge manufacturers adopted a new method of describing cartridges based upon the diameter at the head and mouth of the cartridge. Thus the No. 56 Spencer cartridge (.52 caliber) became the .56-.56 and the new 50 cal. round became the crimped cartridge .56-50 and the tapered .56-.52 cartridge. Both cartridges were used interchangeably in all post-CW .50 caliber Spencers.

The .56-.50 cartridge was actually designed by the Springfield Armory in late 1861 and was intended to be used in the Spencer Model 1865 repeating carbine. However, the rifle and cartridge were manufactured too late for use in the Civil War but many were issued to troops fighting indians on the western frontier.

According to Frank Barnes’ Cartridges of the World, Christopher Spencer did not care for the .56-.50 cartridge believing it had an excessive crimp around the bullet. He apparently refused to advertise the .56-.50 in Spencer catalogs and beginning in 1866,. he designed a slightly tapered .50 caliber cartridge that became known as the .56- .52.

The new .50 caliber Spencer cartridges began to be manufactured at the very end of the Civil War, headstamps began to appear on the cartridges of several Spencer cartridges subcontractors. Spencer never headstamped their cartridges. Deane Thomas has written in his book, Roundball to Rimfire that headstamped specimens of .50 cal. Spencer cartridges are known to exist from all six “war-time” cartridge subcontractors. Thomas points out that based upon the dates of all deliveries of .50 cal. Spencer cartridges, headstamping of these cartridges first occurred in June of 1865. Most of these cartridges found their way to the western frontier after the War.

Spencer

cartridges were manufactured to the early 1900s. These

old cartridge

illustrations show the various types of Spencer cartridges. Post Civil

War .50

caliber Spencers were used during the Indian Wars and were manufactured

by

several companies. All of my cartridges were of the .56-.50 type.

My

Casings

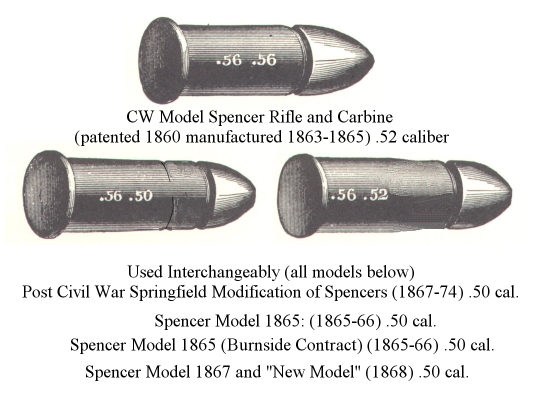

Armed with the above knowledge, I commenced to examine my cartridges. All had .56-inch base diameters but the mouth of the cartridges all had crimping and tapering to .50 inches. This means the cartridges were .56-.50. A pronounced crimp mark on the casings further indicated that they were .56-.50s rather than the slight taper of the .56-.52s.

Subcontracted Spencer .56-.50 casing showing crimping around bullet. Also seen is faint curved breech drag impression created as casing was ejected or inserted. The location of other breech drag marks around the casing probably reflect individual weapons that can be compared and matched.

Closer examination of my cartridges showed post Civil War headstamps of Joseph Goldmark, NY. (manufactured rimfire cartridges from 1857 to 1866); Van Vechten & Company, NY. (1864-1871); and Sage Ammunition Works, CT. (1864-1867). Christopher Spencer never headstamped his cartridges.

Three period headstamps from various rimfire cartridge manufacturers purchased by the author.

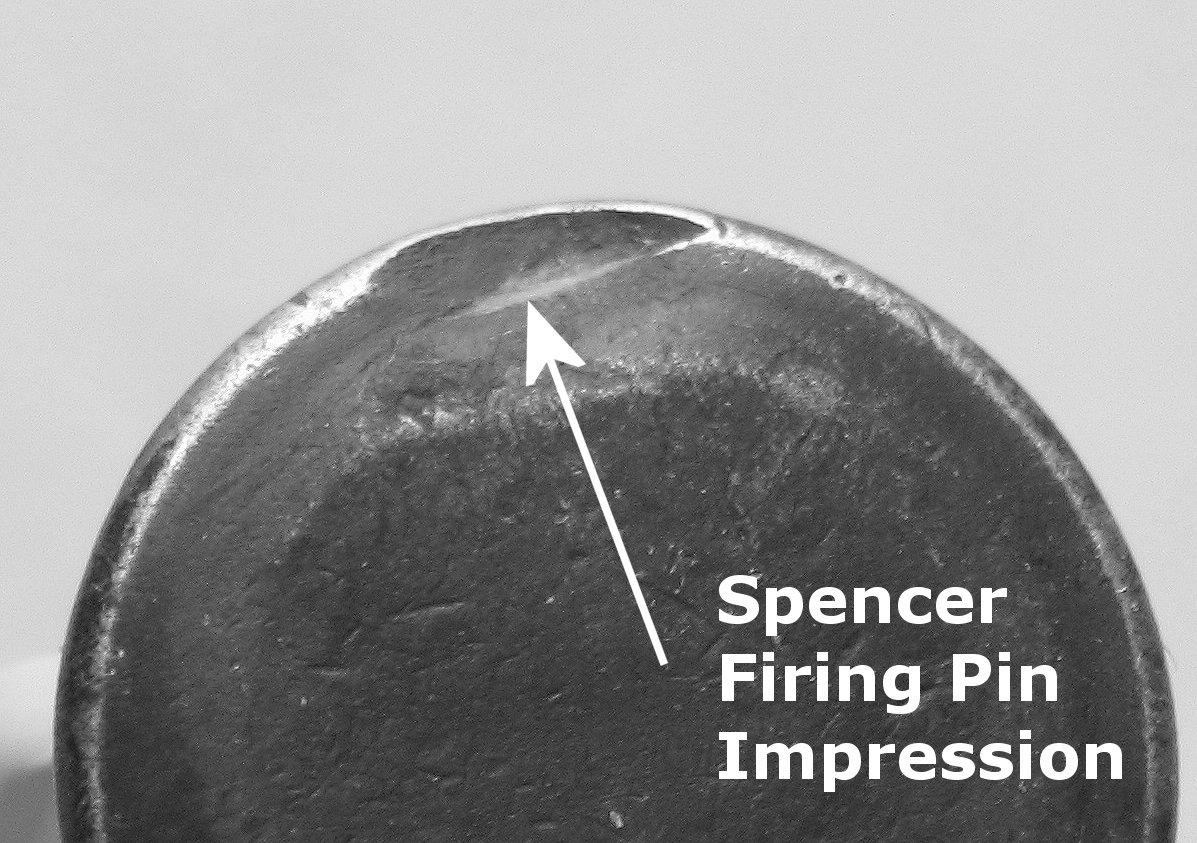

Firing

Pin Impressions

All of my

casings had the curved firing pin impression that is sometimes a little

deeper

on one end. All of my casings had the same firing pin impression and

extractoror

marks.

Spencer firing pin impression on Spencer casing (no headstamp)

Casing

Extractor Marks

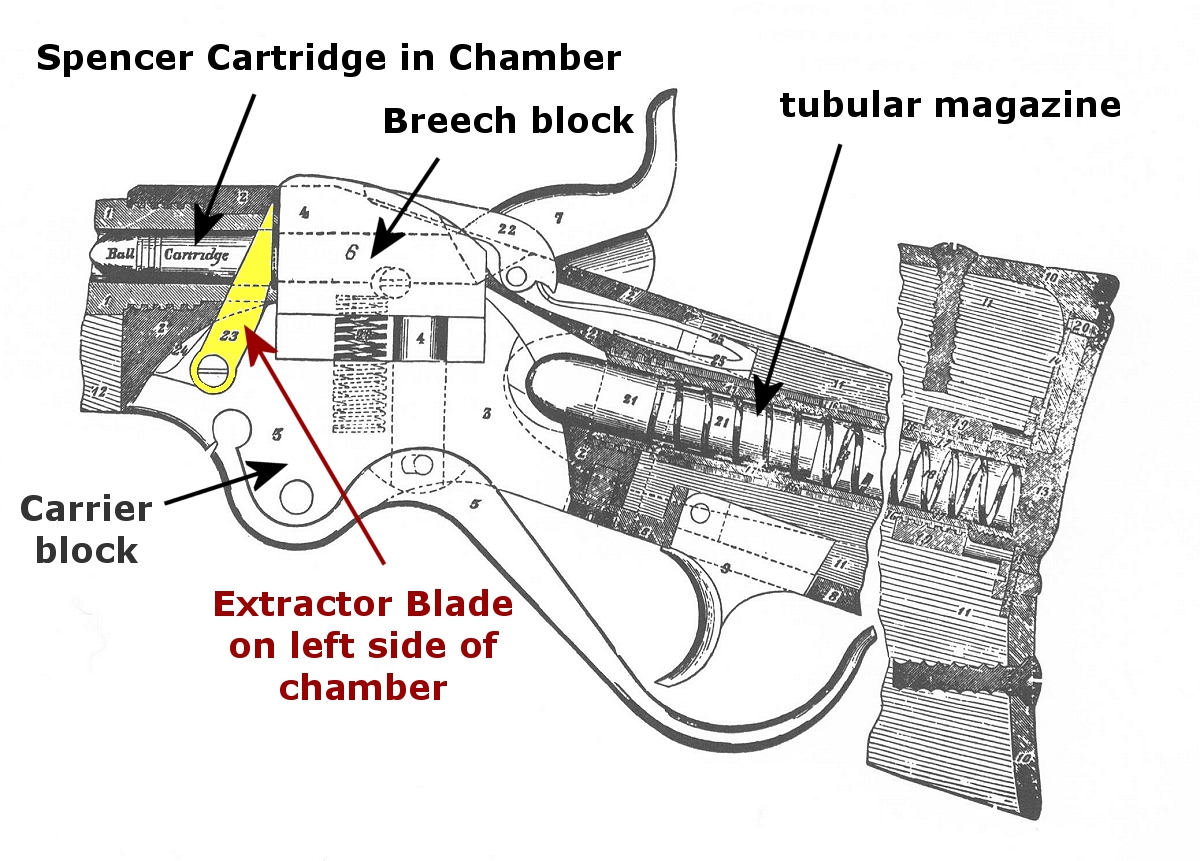

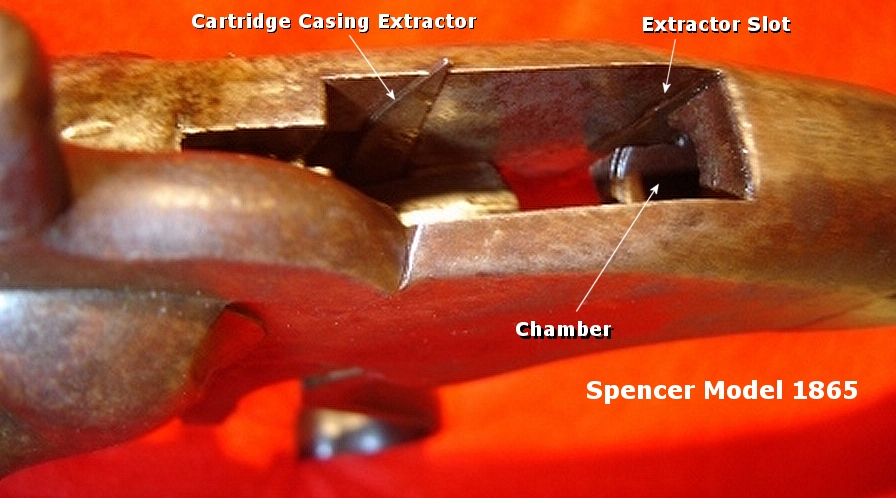

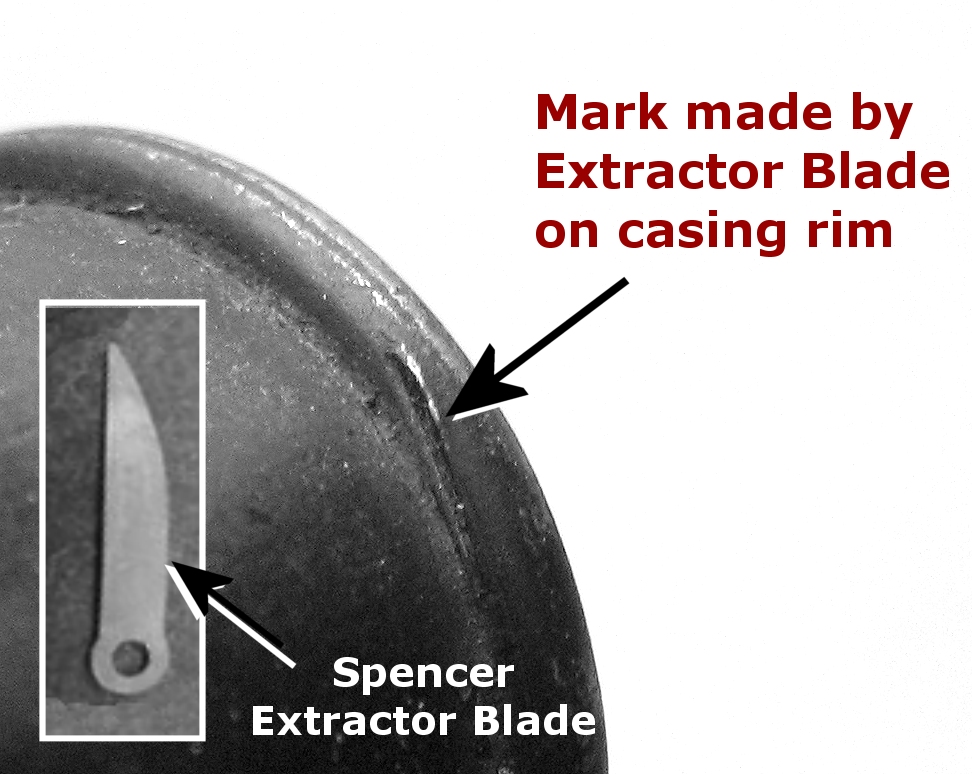

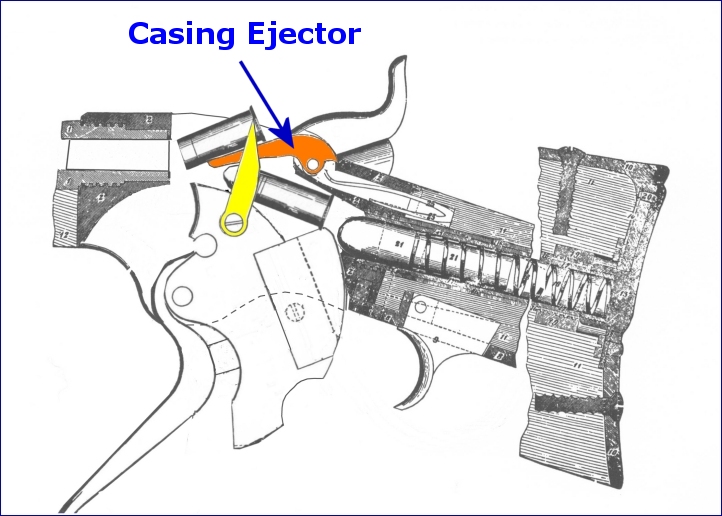

The Spencer extractor marks are found on the inside edge of the casing rim exactly opposite the firing pin impression and are the result of the long extractor blade (Part 23 in figure below) gripping the left edge of the fired casing as the weapon is cocked. Normally the blade resides in a slot just to the left of the firing chamber. As the lever action is moved foward, the breech block moves down and is rotated toward the tubular magazine .This action also allows the extractor blade to grab the spent casing left rim edge and ejecting it from the chamber and out of the weapon. This action makes a slight cut mark on the inside rim of the spent casing. A new cartridge is moved into the chamber from the tubular magazine.

All of my casings except one (a possible misfire) had the same extractor marks in the same location on the rim with respect to the firing pin impression. This implies that they were all fired from a .52 caliber Spencer Model 1863 (barrel sleeved at the Springfield Armory to .50 caliber) or from the newer .50 caliber Spencer Model 1865 carbine.

Extractor blade mark on inside edge rim of Spencer cartridge opposite firing pin impression found on the outside edge of the casing rim. INSET: Spencer Extractor blade.

Spencer expert and Civil War reenactor Tony Beck in various articles has stated thet the greatest difference between the various Spencer models is the cartridge extraction system. Model 1863 and 1865 Spencers used a long blade on the left of the breech block carrier (shown above) . In the Model 1865, this blade is held forward with a helper spring to make single loading easier and in Spencer Model 1867, the Lane patent extractor, a spring loaded tooth mounted on the centerline of the breech block carrier was used. Spencer Models 1868 ("New Model") utalized a short blade relocated to the left of the breech carrier block.

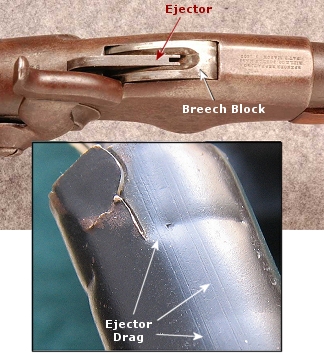

Casing Ejector Drag Marks

When the lever handle of the Spencer was moved forward, the breech block was pulled down against a vertical coil spring located within the breech carrier block. This allowed the mechanism to be rotated. The spring loaded casing ejector was urged downward as the breech block went down. The ejector formed a ramp for the extracted shell casing. The extractor blade then threw the casing clear of the action. When the carrier block was fully rotated, a new cartridge was pushed ahead of the breech block from the tubular magazine. As the lever action was closed, the fresh cartridge rode under the casing ejector as it guided the cartridge into chamber (see figure below). This action sometimes created ejector drag marks down the entire length of the casing as shown below.

Two sets of parallel grooves made down the length of the casing as the ejector guided a fresh cartridge into the chamber.

Possible

Tubular

Magazine Detonation

One of my casings has no firing pin impressions and appeared to be torn right at the bullet crimp. Drag marks were also not present on the casing. Closer examination of the lip of the tear indicated that the edge was bent outward. Two possibilities could explain these observations. First, the bullet might have been extracted from the casing with a knife perhaps for its powder (maybe to start a campfire). Or, second, it could have been a premature detonation in the tubular magazine when the nose of the bullet directly behind this bullet in the magazine came in hard contact with the base of the bullet shown below causing it to go off. This could happen if the carbine was accidentally dropped on its butt end.

Possible premature detonation of Spencer bullet in tubular magazine as a result of coming into hard contact with other bullets in magazine. The .56-.50 casing (note crimp) had no firing pin impression.

What can the relic hunter take away from this discourse? First, weapons firing Civil War Spencer cartridges (.52 caliber) each had unique firing pin and extractor/ejector impressions but no headstamps. Headstamps on Spencer cartridges (.50 caliber) that were used in the Indian Wars were manufactured at the end of the Civil War through the 1870s. Post Civil War Spencers also had unique firing pins and extractor/ejector.impressions that are model dependant. The impressions shown in this article are from the Springfield altered Spencer Model 1863 or the Model 1865.

Breech drag marks are weapon-unique. Cartridge casings fired from the same weapon can be matched and traced across a relic field by their identical casing impressions.

Like what you read? You can find more techniques like this in my books and CDs. DP

Good Additional Readings:

Tony Beck, "Spencer's Repeaters Some History and Shooting Tips" at: http://www.awod.com/gallery/probono/cwchas/spencer.html

David F. Butler, "United

States Firearms The First Century 1776-1875", ISBN

0-87691-030-04

Joseph G. Bilby, "Civil War Firearms", ISBN 0-938289-79-9

Frank C. Barnes, "Cartridges of the World", ISBN 0-87349-605-1

Norman Flayderman, "Flaydermann's Guide to Antique American Firearms",

ISBN 0-837349-198-X

Dean S. Thomas, "Round Ball to Rimfire", Part 2 , ISBN 1-57747-020-6

Douglas D. Scott et al, "Archaeological Perspectives on the Battle of

the Little Bighorn", ISBN 0-8061-3292-2