By dawn on April 7,

the combined Federal armies numbered 55,000 men. Beauregard, unaware that all of

Buell's army had arrived, planned to continue the attack and drive the Northerners into

the river. At 6 a.m. the Confederates went on the offensive and were, at first,

successful. The stronger Union armies, however, soon began to push the Confederates

back. Realizing that he had lost the initiative, Beauregard tried to break the Union

drive by counterattacking at Water Oaks Pond. The Federal advance was stopped, but

their line did not break. Low on ammunition and food and with 15,000 of his men

killed, wounded, or missing. Beauregard knew he could go no further. He

withdrew beyond Shiloh Church and began the weary march back to Corinth. The

exhausted Federals did not pursue. The battle was over.

|

On April 8, Grant sent Sherman south along the Corinth Road to try to catch

the retreating Confederates. Ten miles out he ran into the Southern rear guard under

Col. N.B. Forrest. Sherman abandoned the pursuit.

|

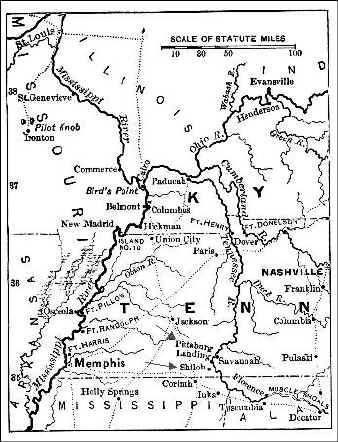

In late April and May

the Federals crept toward Corinth and seized it, while an amphibious force on the

Mississippi was destroying the Confederate River Defense Fleet and capturing

Memphis. From these bases the Federals pushed down the Mississippi to besiege

Vicksburg. After the surrender of Vicksburg and the fall of Port Hudson in Louisiana

in the summer of 1863, the Confederacy was effectly cut in two. The war went on.

|

In terms of the Poche

Family, the majority of the family was in the 18th Louisiana Infantry and the 30th

Louisiana Infantry. The 18th fought at Shiloh, Mississippi in 1862 and exactly two

years later to the day, it was fighting at the Battles of Sabine Crossroads (Battle of Mansfield) and Pleasant Hill in western

Louisiana. At both battles, the 48th Ohio Veteran Volunteer

Infantry was also engaged. To get a different perspective about life "on

the other side" read their Regimental

History.

|

The plight of the Pochés of

the 18th Louisiana at Shiloh was described in the Journal of the Orleans

Guard:

|

"6th-At 5 o'clock ordered into

line of battle; marched to and fro until 8, through woods and fields. At about

half-past 8 passed through the abandoned camp of the 6th Iowa. Found there a

bountiful supply of bread, hot from the oven, any amount of provisions, wine, fruits, and

other delicacies; enough all together to feed ten regiments. Halted there for a half

hour. Passed soon after to another camp, abandoned by its occupants at our approach,

not without their firing a parting volley. The Crescent [Crescent Regiment] at this

camp diverged (owing probably to the dense woods) from the line of march of the Orleans

[Orleans Guards Battalion] and the 18th Louisiana. After half an hour's march

further on, just as it was preparing to assault another camp, it was assailed by a brisk

musketry fire, which proved to be from the 6th Kentucky and a Tennessee regiment.[27th

Tennessee Infantry] These troops, at sight of the blue uniform brought out

from New Orleans, mistook the Battalion for the enemy. Two men were killed by this

error.

|

At five o'clock joined the 18th La. in

a ravine, about half a mile from the Tennessee River. Remained exposed to the enemy's fire

from the plateau of the hill in front of its line of battle, and to the shells of the

enemy's gunboats.

|

The Battalion here awaited the order of

General Preston Pond, who stood twenty yards off; the enemy meanwhile was a half mile from

the Tennessee river, which they had fortified. They were now awaiting our attack,

having already repulsed that of the 16th Louisiana.

|